Death, Duty, and Faith: Stewart O’Nan’s “A Prayer for the Dying” in the Age of Coronavirus

“I’m doing the best I can,” he says, “but there are just too many of them. And even if it was just one or two, there’s not much I can do for them. Do you understand me?”

“I understand,” you say….

“I know you know, Jacob,” he says, and yawns hard, rubs his face with both hands so it goes red. “It’s just hard to watch it happen.”

Novels and movies about pandemics and epidemics are enjoying a resurgence right now, as large swaths of the American public stay inside to avoid spreading the coronavirus COVID-19. For movies, Contagion seems to be the favorite, while Station Eleven appears to be mentioned more than any other novel. While I’m a sucker for a good post-apocalyptic tale and a fan of Station Eleven, the epidemic novel I found myself wanting to revisit in America in March 2020 was A Prayer for the Dying by Stewart O’Nan.

I’m a huge admirer of O’Nan’s, and have read nearly all of his books, right up through last year’s Henry, Himself. A Prayer for the Dying was the book that first introduced me to his work — I think I must have read it not long after it was first published in 1999. My memory of some plot details was hazy, but I’ve carried with me incredibly sharp, visceral memories of certain scenes.

It was also the first novel I read written using the second-person point-of-view — so “you” become the protagonist. As I’ve discovered since, this is a difficult trick to pull off. Still, in A Prayer for the Dying, I was emotionally blown away by O’Nan’s skill, so much so that I have never since been able to bring myself to re-read the novel, concerned it wouldn’t hold up to that earth-shaking first reading. Now, though, I figured, was the time to try.

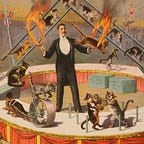

A Prayer for the Dying is the story of Jacob — constable, undertaker, and pastor of the small town of Friendship, Wisconsin, just after the Civil War. As a man prone to questioning, Jacob wears his multiple hats uneasily, but deeply believes the town and all its residents are his mission, his charges, to be protected at all cost.

“At all cost” is a phrase that holds more and more significance as the plot spins out. Jacob is a measured and thoughtful man, but O’Nan skillfully provides first hints, then concrete evidence, of a past that troubles his mind. It’s an acknowledgment of O’Nan’s skill as a writer that I can’t really say much more without ruining his complex narrative tapestry. Suffice to say that Jacob has made difficult choices in his life and not all sit easily with him, nor with his efforts to be a good man in trying times.

For Friendship is indeed soon beset. At the beginning of the novel, Jacob is called out to attend to a dead man in the woods, and then encounters a woman in both a religious and literal fever. Doc, the town’s physician and Jacob’s friend, diagnoses both as stricken by diphtheria — contagious, easily transmissible, and deadly. When he hears the news, Jacob thinks: “…of the disease itself you’re mostly ignorant. It kills, that’s enough.”

O’Nan, in an understated way that seeps slowly into the reader’s consciousness, documents the horrifying disease transmission vectors we all are so familiar with right now — claps on the shoulder, coughs, sneezes, the exchange of goods and money, handshakes, hugs, and kisses. Infection rips through the town and its environs as Jacob and Doc struggle to balance their duty to their neighbors with the larger duty to keep the disease contained, a balance that gets more morally challenging as time goes on and the epidemic spreads. Do you quarantine the town, not allowing anyone in or out? Do you forcibly confine the sick to their homes? Is it safe to embalm the dead or do you deny them and their families that last comforting ritual?

It becomes clear that good responses that protect both the individual citizens and the larger society are in short supply. Individual incidents where duty, even if clear, is horrifying, shake both Jacob and the reader, already bonded through the second-person point-of-view. Jacob is shaken and you are shaken.

This prompts moral questioning. Jacob has a beautiful wife, Marta, and a young daughter, Amelia, neither of which he believes he deserves: “…sometimes you wonder if they need you at all, if you’re really a part of them. It’s fleeting, this worry, and turns quickly into wonder at how lucky you are. Certainly you’re unworthy of such love.” Jacob struggles to be a good man, protect his family and his town, and keep his faith, while his past gnaws at him and increasingly dire circumstances don’t provide a clear and ethical path forward.

It’s this feeling of being in a place where choices begin to muddy and swirl and options start to seem less and less clear that resonated to me as I re-read A Prayer for the Dying while “social distancing” in my home in 2020. How in a time of calamity does one balance the needs of society with the needs of the individuals who live in it? Jacob (and you) face this question when he announces a quarantine:

All morning the quarantine brings town out of their houses. To challenge it, to complain of the decision, dispute its usefulness, its legality. They come to you with questions you can’t answer, though out of politeness — out of duty — you try….

“I’ve got a shipment of coffee sitting in Shawano I can’t get to.”

“Have them ship it.”

It’ll cost too much to ship.

Mrs. Bagwell’s daughter is stuck in Shawano.

Carl Huebner was off on business, and now he can’t get back in.

And George Peck, down to Rockford buying brick for the mill.

Why can’t they come in if they want to? It’s their risk, no one else’s….

…“It’s the right thing and you know it.” Then to everyone: “Two weeks is not a long time.”

Grumbling, an obscenity that — admit it — shocks you. No one believes you. Two weeks is a lifetime….

You’re right, you think, it is the right thing. Why do you have to justify it?

We’re seeing this play out in real life in 2020, as we seemingly have to choose between staying inside and keeping our jobs, between risking the lives of our medical providers with inadequate protective gear and not having medical care at all, between laying off employees and going out of business entirely, between withholding ventilators from the weakest patients and not being able to provide ventilators to those who are more likely to recover, between going to the grocery store and protecting our families. If you haven’t yet had to make a morally hazy choice during this pandemic, you will.

Jacob tries to live in this gray area, to embrace it:

“You’re proud of your ability to both believe and question everything. Secretly you think everyone does, but at some point they give in, surrender to the comfort of certainty. It’s too much trouble, this endless jousting of belief and doubt, too tiring. Finally you suppose it will break you, yet strangely it’s the only thing that keeps you going — though, true, at times you feel unbalanced, even somewhat mad.”

One of the things that keeps him going is that he empathizes with the people of Friendship. He understands when they get angry with him, when they violate quarantine, when they defy orders intended to keep them safe. He worries (“Worry rolls inside you like a wheel”), but he understands. As the man sworn to keep them safe, both physically and spiritually, and in addition, to see them to their eternal rest, he owns their well-being from cradle to grave.

But his own well-being is much more tenuous. The demons from his past that he’s struggled to move beyond haunt his every minute in this new, uncertain world. The traumas of his Civil War soldier past reemerge as Jacob has to deal with the increasing magnitude of the dead. Every new decision makes him question whether he is, indeed, a good person, and whether life is, indeed, worth the anguish it brings. His faith is repeatedly shaken.

I’m reminded of all those in 2020 whose existence is precarious in one way or another — those living paycheck to paycheck, those struggling with depression or anxiety, those who have family members with special needs, those who may be questioning their own faith or their own goodness. None of us enters this crisis free of baggage — we bring our whole selves, selves often balancing on a razor blade.

I suppose that’s another reason why, even if you are avoiding epidemic-based stories during the coronavirus crisis, you might think about picking up A Prayer for the Dying. Don’t get me wrong — it’s grim. And there are scenes that will stay with you for years, if not decades, in their stark horror. But the grimness, for me at least, is leavened by this idea: Humans will fight like hell to do the right thing. And even when we make the wrong call, we still go on. We are fragile, we may be crippled, we may dance along either side of that razor blade, but we are hard to permanently break.

With duty, with faith, and with empathy — we will go on.